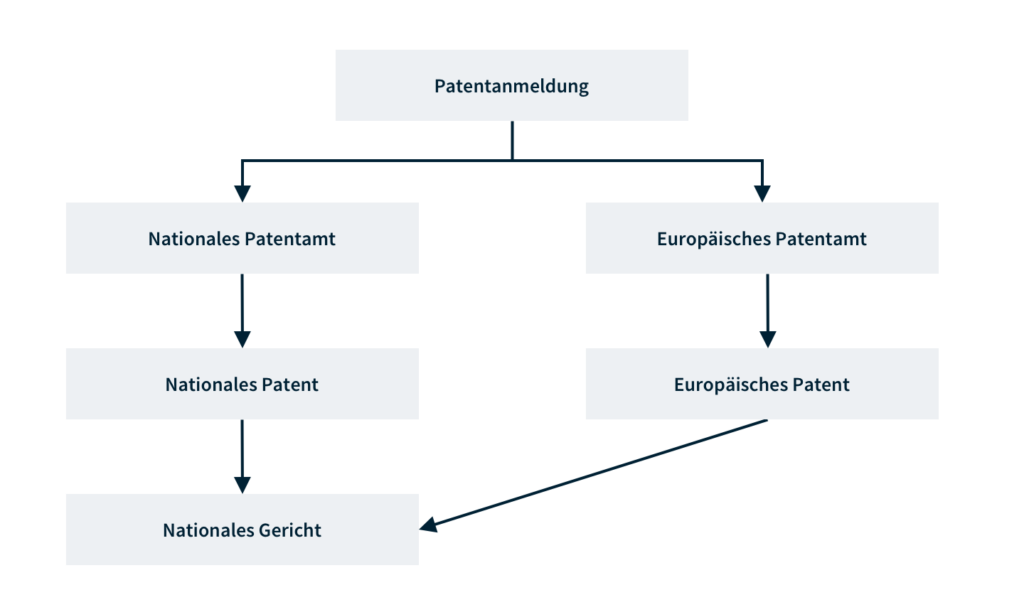

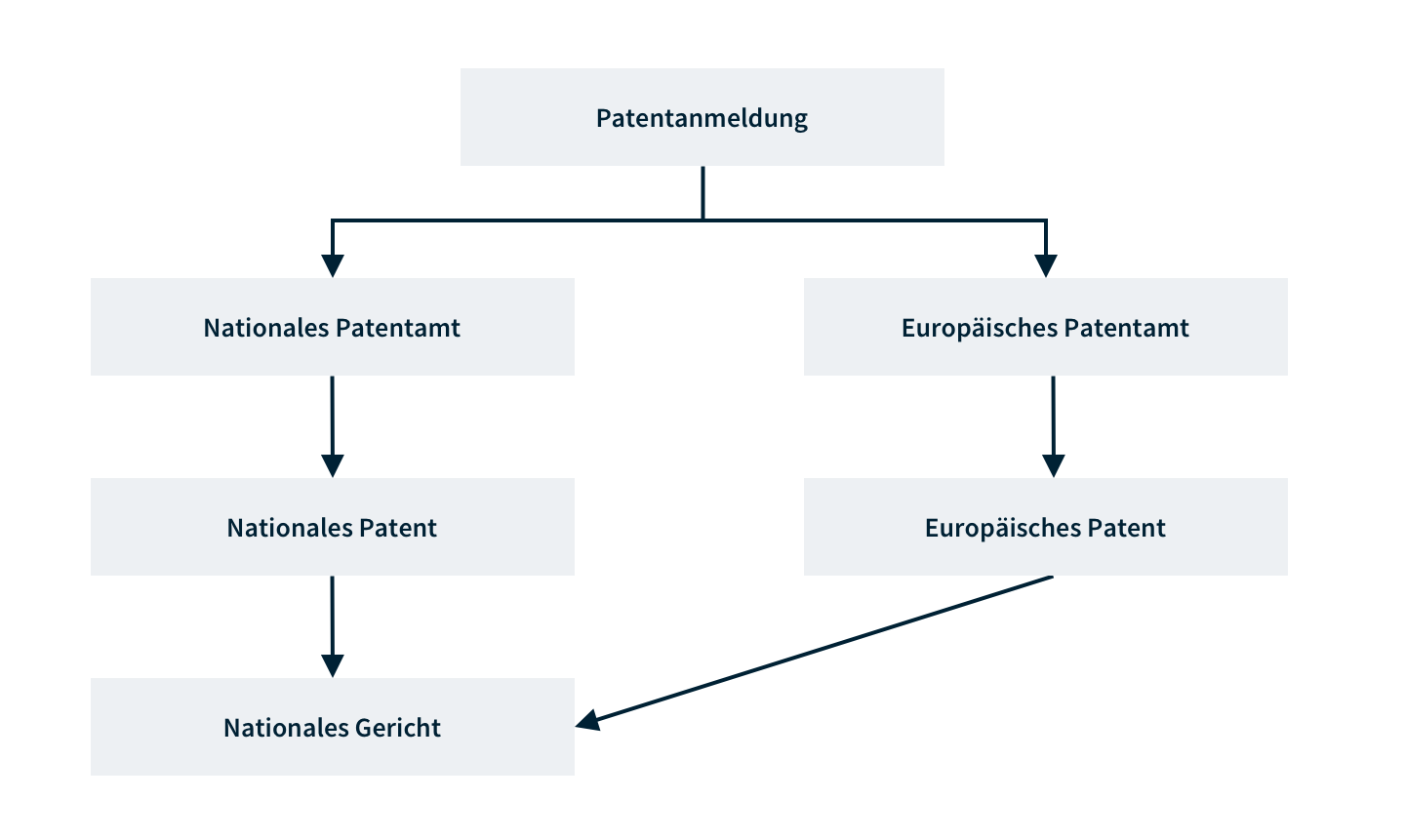

In principle, the introduction of the so-called “Unitary Patent” (European patent with unitary effect (UP)) initially changes nothing. A patent application can still be filed in Europe via national patent offices and/or via the European Patent Office, with a corresponding national or European patent being granted after a successful prosecution. Once granted, the European patent is known to split into national parts (“bundle of national patents”). Legal disputes concerning national patents or national parts of European patents will continue to be heard before the respective national courts (see schematic diagram below).

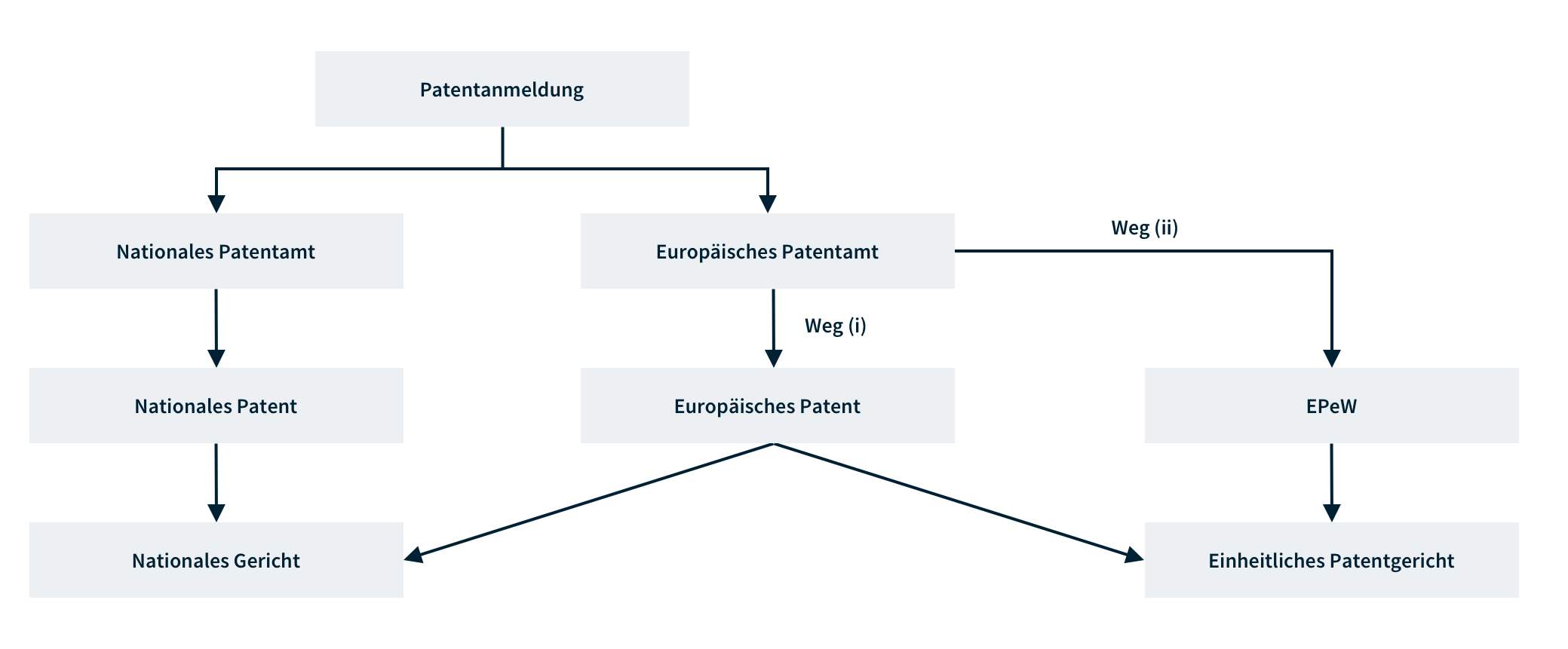

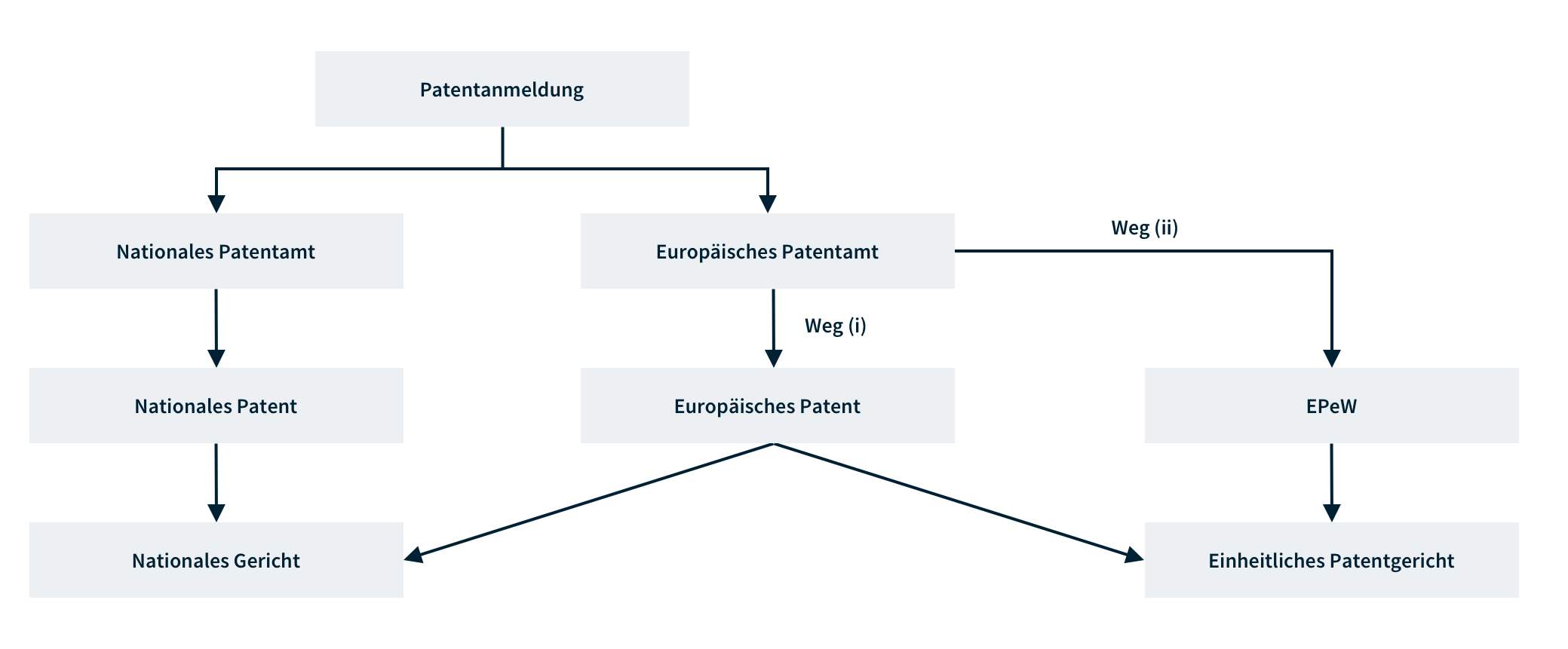

The Unitary Patent offers a new, additional option which complements the existing European patent system rather than replaces it. The applicant can now, upon grant of a European patent, choose between two options (Route (i) and Route (ii)).

Under Route (i), everything remains unchanged: upon grant, the European patent splits into a bundle of national parts.

Path (ii) is a new option where the Unitary Patent can be applied for, which currently covers 18 Member States (24 Member States are planned in the long term) of the European Union (EU). This will allow a single patent to be granted with unitary effect in all of these currently 18 EU Member States, instead of the previous 18 national parts of the bundle patent.

In Member States of the European Patent Convention (EPC) which do not participate in the Unitary Patent, the bundle patent of national parts can still be used in parallel. If Route (ii) is chosen, there is no longer a national part of the European patent in the states participating in the Unitary Patent. However, a corresponding national patent with the same scope of protection may exist (no prohibition of double patenting).

The following schematic diagram shows how the Unitary Patent (UP) complements the previous system shown above. It is important to note that legal disputes (particularly patent infringement proceedings and patent nullity proceedings) concerning the Unitary Patent can exclusively be brought before the new Unified Patent Court (UPC). In principle, national courts do not have jurisdiction over a Unitary Patent. In principle, national courts do not have jurisdiction over a Unitary Patent.

First of all, the Unitary Patent can be interesting for cost reasons. If 18 countries are covered by a single patent, the respective national renewal fees, translation fees and costs of national representatives are waived. The renewal fees for the Unitary Patent are calculated based on the combined renewal fees of the largest European filing countries at the time of drafting the legal basis for the Unitary Patent, namely Germany, France, United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Even though the United Kingdom will not participate in the Unitary Patent after Brexit, the costs have not been reduced as a result.

It is therefore reasonable to conclude that, in terms of costs, a Unitary Patent is only worthwhile where filing takes place in four to five countries. If, for example, validation is merely to be carried out in Germany, France and the United Kingdom (the latter not being a state participating in the UP), the costs for a Unitary Patent will likely be significantly higher than for the national parts of the bundle patent. If, however, in contrast, the bundle patent was to be validated in, for example, ten states participating in the Unitary Patent, it presents a highly interesting alternative to the national parts in terms of costs.

If patent infringement proceedings are to be expected in several European countries, they can be bundled in a targeted manner in one procedure via the Unitary Patent. In principle, only one infringement proceeding (for all participating states) is envisaged for a Unitary Patent. Thus, court costs can be reduced, and procedural efficiency enhanced. Further, this may result in timely decisions in countries where experience has shown that the courts work very slowly.

The Unitary Patent can also serve as a tool to obtain the exclusive jurisdiction of the Unified Patent Court in legal disputes or to exclude the jurisdiction of national courts.

On the other hand, the Unitary Patent can be declared invalid by the UPC in all 18 participating states at the same time through a single invalidity procedure. While it may be advantageous for strong patent rights to be subject to only one central nullity proceeding, the risk of losing the patent completely may be considered too high for weaker patent rights.

Particularly in the case of valuable patents, it may therefore be advantageous to obtain national patents in parallel to the Unitary Patent. As mentioned above, a national patent may coexist with a corresponding Unitary Patent, even if the scope of protection is the same. In case a national patent and a corresponding European patent with the same scope of protection are granted (in which case the so-called double patenting prohibition applies), a Unitary Patent could be chosen after grant by the European Patent Office, and the national patent and the Unitary Patent can exist in parallel (no double patenting prohibition).

The previously available ways of enforcing and revocation of patents will remain in force. In principle, nothing will change at all for the time being. Legal disputes (in particular patent infringement proceedings and patent nullity proceedings) concerning a national patent or the national part of a European patent will continue to be heard before the respective national courts (see schematic diagram below).

In fact, the UPC has the potential to significantly change the existing European patent system as the UPC interferes with the existing system in two important ways:

i) The Unitary Patent offers a new, additional option, which does not replace the existing European patent system but rather complements it. Legal disputes concerning the Unitary Patent will be heard exclusively before the UPC. National courts do not have jurisdiction over the Unitary Patent.

ii) In addition to legal disputes concerning the Unitary Patent, the UPC offers a second option which is not immediately obvious but of enormous significance: the UPC has jurisdiction over legal disputes concerning ANY national part of a European patent of the currently 17 UPC Member States. This means that from the time the UPC commences its activities, the claimant can choose whether such legal dispute is to be heard before a national court or the UPC. If a lawsuit has been brought before the UPC, it has jurisdiction and the route via national jurisdiction is blocked.

Currently, 18 member states (24 member states are planned in the long term) of the European Union (EU) participate in the UPC. These are the same states that also participate in the Unitary Patent. However, while the Unitary Patent is governed by two EU regulations, the UPC is based on the so-called Agreement for a Unified Patent Court (UPCA), an international treaty (similar to the European Patent Convention, EPC). However, substantive law of the EU regulations is outsourced to the UPCA, so that the Unitary Patent and the UPC are inseparably intertwined.

The schematic diagram below shows how the UPC or the European patent with unitary effect (UP) complement the previous system shown above. It is important to note that legal disputes (in particular patent infringement proceedings and patent nullity proceedings) concerning a Unitary Patent can exclusively be heard before the new UPC. In principle, national courts do not have jurisdiction over a Unitary Patent. However, for national parts of European patents in the UPC Member States, the UPC also has jurisdiction, in addition to the national courts. Thus, there exists a concurrent jurisdiction.

Firstly, proceedings before the UPC can be interesting in terms of costs and efficiency. Patent protection via the Unitary Patent initially saves annual fees compared to corresponding national parts of a European patent (a cost saving is generally possible compared to validation in around four or more states of a European patent). Since a single patent infringement action or patent nullity action currently covers up to 18 states, it is already clear that enormous court and legal costs can be saved, especially in the case of high amounts in dispute. A single court decision (as opposed to up to 18 individual decisions) also avoids contradictory decisions.

If patent infringement proceedings are to be expected in several European countries, they can thus be bundled in a targeted manner via the UPC. Furthermore, efficient proceedings can also be enabled in countries where experience shows that the courts work very slowly. However, the United Kingdom, which is important for patent disputes (and has so far been very costly), does not participate in the UPC.

Corresponding to a single patent infringement proceeding, there is also only one nullity proceeding before the UPC. The European patent can thus be declared invalid in all 18 participating states at the same time by means of a single invalidity procedure. While it may be advantageous for strong patent rights to survive merely one nullity proceeding, the risk of losing the patent completely may be considered too high for weaker patent rights.

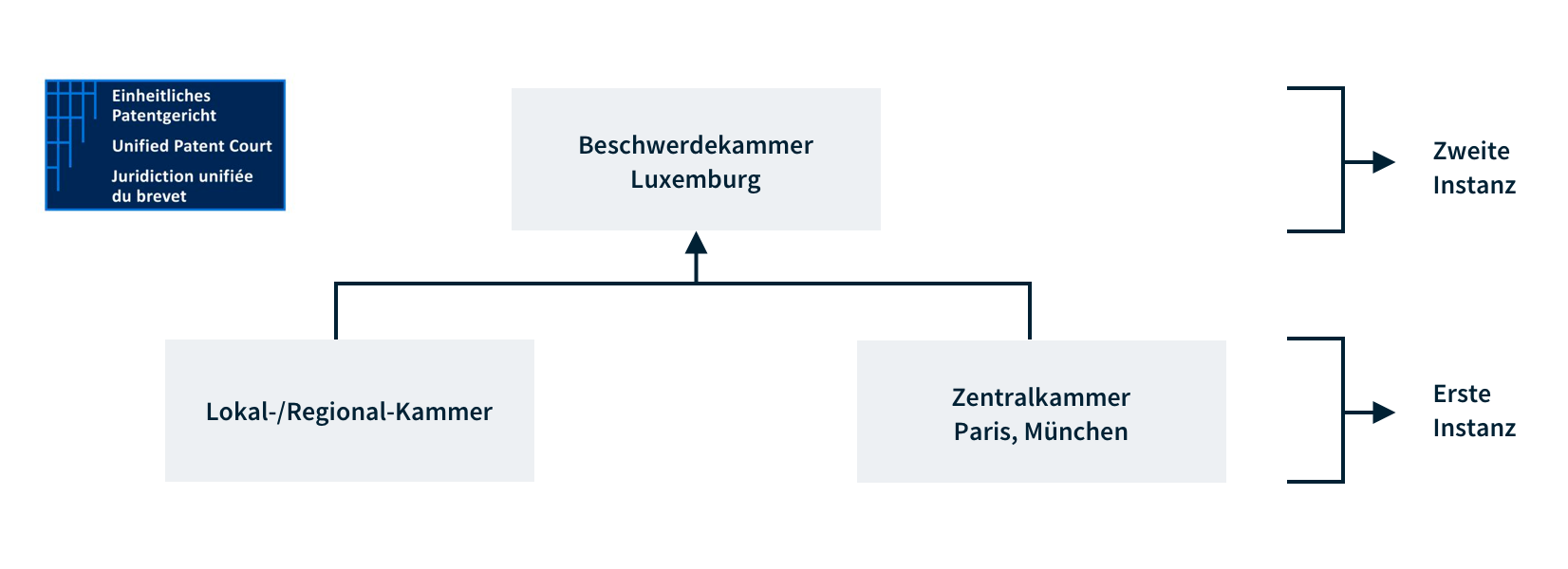

The UPC comprises two jurisdictions at first instance between which the claimant can choose:

(i) a Local or Regional Division, and

ii) the Central Division, which is seated in Paris or Munich, depending on the technical area.

While infringement proceedings can be brought before both jurisdictions (and nullity counterclaims are possible), isolated nullity proceedings can only be heard before the Central Division.

The Local/Regional Division is a designated jurisdiction of a UPCA Member State with great experience in patent litigation. Germany has the largest number of Local Divisions being seated in Düsseldorf, Munich, Mannheim and Hamburg.

The second instance is the central Court of Appeal in Luxembourg. According to the UPCA, the UPC is a court of the EU and thus entitled or obliged to refer requests for rulings to the European Court of Justice (ECJ), so that the latter could constitute a further instance. However, this has not yet been clarified.

This is not necessary. After the UPCA has entered into force, the UPC is automatically responsible for every European patent (with at least one national part in the 18 UPCA member states). However, the jurisdiction of national courts cannot be excluded.

Yes, at least for the first seven years after the UPCA entered into force via the so-called “OPT-OUT” option: a European patent can be excluded from the jurisdiction of the UPC by means of a request for which no official fee is charged.

From the entry into force of the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (UPCA) on June 1st, 2023 the new Unified Patent Court will automatically have jurisdiction over any European patent. At the same time, however, national courts will retain jurisdiction. It therefore depends on which court (the UPC or the national court) is seized first. However, the jurisdiction of the UPC over a European patent can be specifically excluded. For this purpose, a so-called opt-out request must be filed with the UPC (not with the European Patent Office). Every European patent, i.e., also a European patent granted before June 1st, 2023, is automatically pending in the new system and accordingly before the UPC, i.e., “opt-in”. Thus, non-jurisdiction of the UPC must be explicitly requested by means of the opt-out request, whereby this non-jurisdiction can also be reversed if no proceedings (or litigations) are pending. In other words, a later “opt-in” to the jurisdiction of the UPC is possible. It should be noted that an “opt-out” is only possible for “classical” European bundle patents. No “opt-out” can be declared for a Unitary Patent as the UPC has exclusive jurisdiction over the Unitary Patents.

If no opt-out is declared, the patent proprietor has the option to sue before a national court or the UPC (unless a litigation is already pending). Thus, all options remain open for the time being.

The UPC has the “disadvantage” for the patent proprietor that a European patent can be destroyed or restricted in a single nullity proceeding before the UPC (similar to opposition proceedings before the European Patent Office). Valuable patents in particular could here be protected by means of an opt-out as nullity proceedings would then have to be litigated separately in each Member State (as has been the case up to now), which could possibly result in different judgements.

At the same time, however, successful central nullity proceedings before the UPC can also strengthen the patent tremendously and exclude other negative decisions.

Dilg, Haeusler, Schindelmann

Patentanwaltsgesellschaft mbH

Expertise in patent, design and trademark law

Leonrodstraße 56-58 · D-80636 München

Tel.: +49 89 3090756-0 · Fax: +49 89 3090756-29

info@dhs-patent.de · www.dhs-patent.de

Managing Director:

Dr. Andreas Dilg

Ignaz Gall

Dr. Peter Schindelmann

Dr. Jens Pilger

Head office: München

VAT: DE254495972

Tax number: 143/129/70636

Munich Local Court

Specialist areas:

Technical physics

Communication technology

Electrical engineering

Mechanical engineering

Medical technology

Chemistry

Molecular biology/Biochemistry

Biomedicine/Pharmacy

Service:

Analysis of protectability and drafting of property right applications

Searches and legal status information

Conducting and coordinating grant and infringement proceedings

Defending own Intellectual Property Rights and proceeding against third-party rights

Preparation of “Freedom-to-Operate” expert opinions

Supervision of “due diligence” procedures and evaluation of intellectual property rights

Drafting of license and R&D contracts

To provide the best experience, we use technologies such as cookies to store and/or access device information. If you consent to these technologies, we may process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this website. Failure to consent or withdrawal of consent may adversely affect certain features and functionality.